I read a recent article written by Joanne Chianello, a journalist at CBC Ottawa, about the City of Ottawa’s Brownfield’s policy. This policy, which was approved by City Council in 2007, provides grants to developers to encourage the redevelopment of contaminated lands. Her article points out that City Council has approved over $70 million in brownfields grant since 2007. The article further questioned the public benefits resulting from such grants and the absence of any assessment to see if the policy was actually stimulating investment which would not otherwise occur.

The article made me re-think about another blog I thought about writing after my 2014 post on the social housing/condominium market in Ottawa’s downtown neighbourhoods, but I never got around to it. The purpose was to review the City’s financial incentives targeted at residential developments in the downtown area.

In 1994, the City launched the Residential Downtown Intensification (Re-Do-It) program initiative to encourage the residential revitalization in the inner city neighbourhoods which had experienced significant population decline, a trend that was common to all large cities in North America as families moved to the suburbs. As a result, many inner-city residential properties in Ottawa were demolished or allowed to deteriorate or to be replaced by surface parking lots.

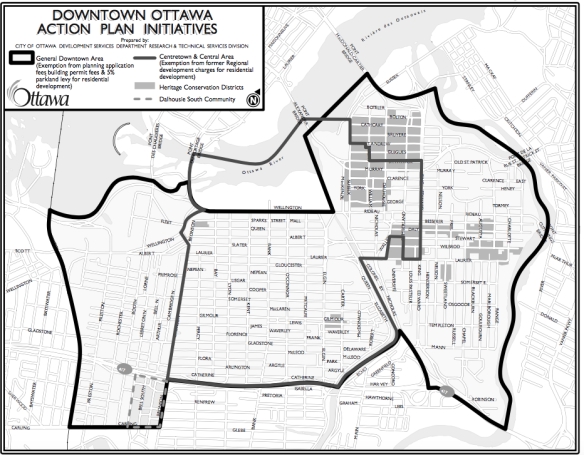

The Re-Do-It program included a waiver on development charges in the targeted inner-city neighbourhoods shown in the following map in an effort to reverse the decline in population. Municipalities in Ontario are permitted, through Provincial legislation, to waive or exempt ‘area specific’ development charges as well as other types of financial incentives, in order to encourage physical development in support of public or social goals.

[Development charges (DCs) are set by the municipality, according to the rules established by legislation by the Province of Ontario, and are collected from developers to help pay for the cost of infrastructure required to provide city services such as roads, public transit, water and sewer, community centres, fire and police facilities, to new developments. The Province requires municipalities to undertake a detailed review and update of their DC By-laws every five years.]

The Re-Do-It program was implemented prior to the 2001 municipal amalgamation when the responsibility of administering development charges fell on the former Regional Municipality of Ottawa-Carleton. The former City of Ottawa also added exemptions from planning application fees, building permit fees and the 5% parkland levy to the larger downtown area.

In 2004, as part of a required 5-year update, the targeted downtown zone was reduced to the Centertown neighbourhood west of the Rideau Canal. The rationale behind this impact boundary change was that Lower Town / Byward Market had experienced significant new residential developments but Centertown was still lagging in experiencing significant revitalization. In 2009, City Council approved discontinuing the area-specific development charge exemption in the downtown but with a two-year phase-in transition period lasting until August 1, 2011, subject to having an approved site plan agreement in place.

According to the FAQs published on the City’s web site 4 years ago but no longer available, the rationale for discontinuing the exemption was that it “achieved its goal of spurring new residential development in the downtown core” and “since the residential downtown intensification initiative was launched in 1994, more than 6,000 new residential units have been built downtown” up to 2009.

That was about all there was in terms of any post-program results or cost-benefit assessment. There was no consideration of whether or not the condominium projects would have been constructed without the exemption although the City’s FAQs does imply anecdotally that it did “spur” new development. I was also unable to find any account of the total value of development charge exemptions to downtown condominium builders.

To estimate the total value of DC exemptions, I applied the City of Ottawa’s 2017 schedule of development charges to the 6,000 units built between 1994 and 2009 in the downtown, and came up with a total DC value that would be over $70 million in today’s dollars (I took the mid-point or average between the $9,978 DC for a one bedroom apartment built inside the Greenbelt and the equivalent $13,553 DC for a two-bedroom multiplied by 6,000 units). I am assuming that all 6,000 units are condo apartments which yields the lowest dollar value since low rise units such as towns and semis which may account for some of the total units, have higher fees (e.g. new townhomes are charged a DC of $18,277).

There exists, however, an earlier report published by CMHC in 2003 that looked at best practices case studies of residential intensification initiatives at that time. According to the chapter prepared by City of Ottawa staff dealing with the City’s downtown residential development fees exemptions, in the 15 months between May 2000 and August 2001, total exemptions equaled about $3.6 million including $2.7 million in development charges exemptions (the rest included waiving of planning application and building permit fees and foregone revenue for cash-in-lieu of parkland fees). The report gives credit to the exemptions program being the primary cause for the revitalization of the downtown housing market. The loss in revenue to the City from the exemptions would, according to the article, be recouped by the increases in property taxes resulting from such developments, typically within four years.

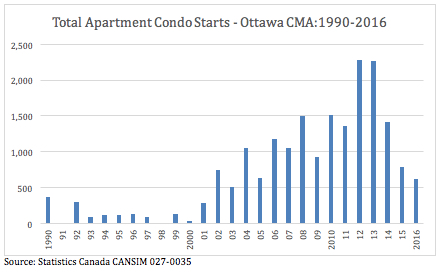

In my analysis below, I focus on the construction of condominium apartments in the Ottawa metropolitan area since such residential developments tend to dominate the real estate market in the inner city in terms of new housing supply. In terms of downtown Ottawa, it is most likely that the majority of new residential construction would consist of condominium units in apartments. The following chart shows the total annual number of condominium apartment unit starts between 1990 and 2016 for the Ottawa census metropolitan area (excluding Gatineau).

The above graph indicates that condominium apartment starts only started to gain momentum after 2001, roughly 7 years after the introduction of downtown development fee exemptions. New construction increased sharply afterward reaching a peak in 2012 and 2013.

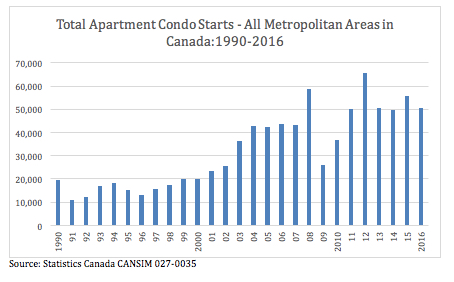

The next graph shows the same data for all census metropolitan areas in Canada. Comparing this graph with Ottawa’s chart reveals that the condominium construction trends are generally similar over the last 20 years except that Ottawa’s market lagged slightly behind the rest of Canada before it picked up in 2002. The downtown condominium construction boom experience in Canada’s metropolitan centres has been attributed to the increased market demand for these types of units on the part of young professionals and childless couples who are attracted to the downtown lifestyle as well as seniors downsizing from the large suburban homes.

The 2012 peak year for all metro areas coincided with Ottawa’s peak which also remained in 2013. The drop in 2009 occurred during the “Great Recession”. However, condominium starts have dropped sharply over the 2014-2016 period in Ottawa but maintained relatively strong steady levels in other metropolitan areas.

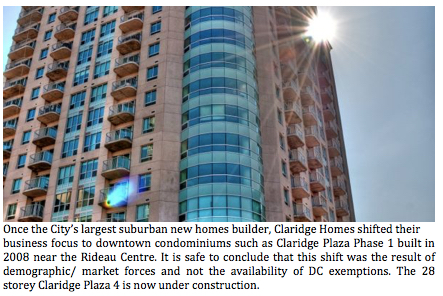

The above comparison of condominium trends does not provide support that Ottawa’s DC exception program was a catalyst for residential revitalization in the downtown. Ottawa’s condominium construction trends paralleled market trends observed in other major Canadian centres. Indeed, the continued run in new starts experienced in Ottawa during 2013 may be the result of builders taking advantage of the exemption before it ended. This, in turn, may have caused the slide in subsequent years due to the overbuilding of new units. Also, the earlier concentration of new housing units in Lowertown/Byward Market compared to Centretown may have had more to do with lower land costs and more opportunities for assembling land and less with the take-up of DC exemptions.

It is also apparent from Ottawa’s trends, that the value of DC exemptions is likely to be well over the $70 million estimated previously which only counted the housing units built in the downtown up to 2009 because the peak years of construction occurred over the next 4 years. The total exemption value may, in fact, be well over $100 million.

So, what does that all mean? First, as stated above, it is very likely that the new condominium towers in Ottawa’s downtown would have been constructed without the City’s development incentives following trends experienced in other major Canadian cities. The policy thinking behind the original exemption program was not based on emerging housing market trends in the inner city neighbourhoods but on an outdated point of view that these neighborhoods in Ottawa were going to continue to lose population and deteriorate.

Second, someone else other than the builders of condominium projects had to pay for the additional cost of municipal infrastructure to support this new growth which is the fundamental rationale for having development charges in the first place. This someone else ends up being other property taxpayers and the waiving of fees simply ends up as a subsidy to builders adding to their profit margin.

Third, the argument put forward by staff and elected officials that the revenue lost from the waiving of fees would be more than recovered from ongoing incremental property tax revenues over time does not hold water. This argument has also been used to support other financial incentives such as brownfields development (view video of Mayor Watson at CBC). Property taxes are collected to pay for ongoing municipal programs and services for all residents and businesses within the city’s geographic jurisdiction. A new condominium project in Ottawa’s downtown, therefore, not only generates one time growth-related costs in terms of new infrastructure but the project’s residents become part of the city-wide pool of taxpayers that consume city services and use city infrastructure (e.g. roads, sewers etc.) on a continuous basis (again, this is the rationale for having property taxes in the first place). The forgone revenue in development fees is therefore never really recovered.

Fourth, the net effect is that the City received very little in community or social benefits in exchange for the reduction of development fees and construction costs to the builder.

I want to conclude by returning to the issue raised at the beginning of my blog as well as in Joanne Chianello’s CBC article which is the absence of any assessment on the part of the City to determine if the financial incentive programs were actually stimulating investment that would not otherwise have occurred or to undertake a public cost/benefit analysis to identify and measure the social or community benefits. With millions of tax dollars involved, one would expect more public accountability. There are other existing financial incentive programs that the City offers besides the brownfield remediation program referred to at the beginning of my blog such as Community Improvement Plans which have been around for close to a decade. These Plans and other incentive programs also require an accountability update. Perhaps this could be considered as an item for the City Auditor’s to-do list.